Tan Dai Nhat

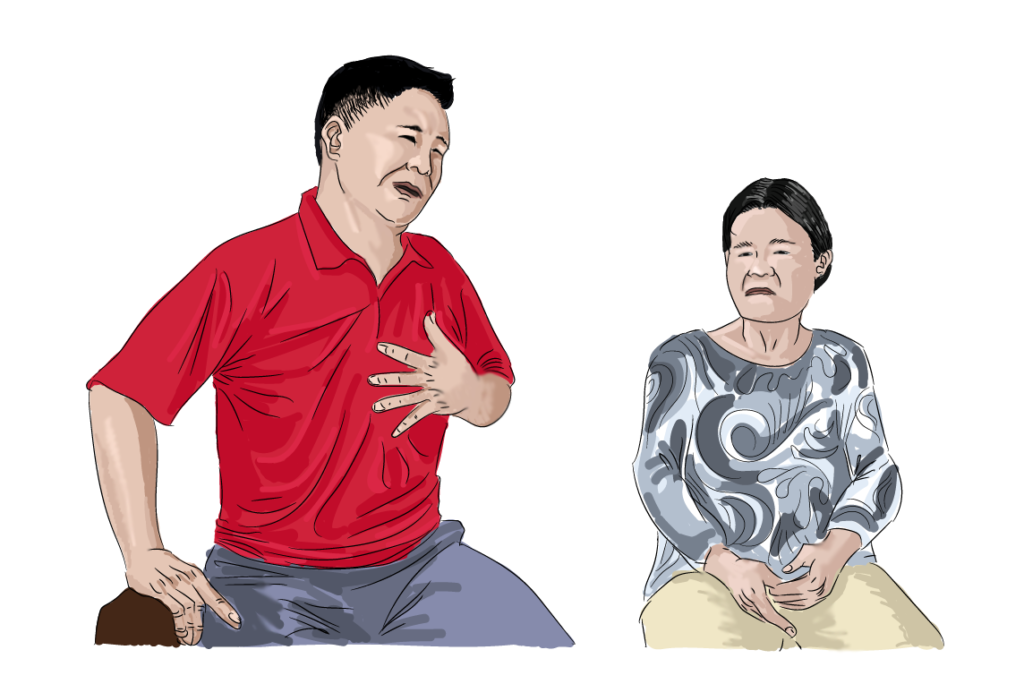

Tran Dai Nhat has lived with stigma, bullying and exclusion from Vietnamese society his whole life without truly understanding why.

The reason is simple, yet unbearable and unfair: his mother, Tran Thi Ngai, was raped, and the rapist is his own father, a South Korean man, who served for Korea in the Vietnam war.

“At school they said I was the son of a ‘dog’. I couldn’t do anything and I never understood why,” Tran Dai Nhat said in an interview for The Guardien.

Like many other Vietnamese women, his mother, Tran Thi Ngai experienced the unimaginable horror of the Vietnam war on her own body. Not by bullets, not by physical battle, but by sexual violence.

“He pulled me inside the room, closed the door and raped me repeatedly. He had a gun on his body and I was terrified,” said Tran Thi Ngai.

The rapist, his father, was a South Korean soldier fighting alongside the US in the Vietnam War. Tran Thi Ngai was only 24 when her country was invaded, and her body suddenly became a battlefield. The children born as a result of this sexual violence are referred to as The Lai Dai Han, meaning “mixed blood” in Vietnamese, a pejorative referring to their mixed Korean/Vietnamese ethnicities.

It is now more than 50 years ago, but like many other women, Tran Thi Ngai had to live – and still lives – with the trauma and stigma that comes with being raped by the enemy, getting pregnant outside the marriage, and giving birth to her rapist’s children. Additionally, the children have been suffering the consequences of their mothers’ tragic history, facing exclusion, bullying, and lack of acknowledgment from the Vietnamese society.

Nguyen Thi Thanh

LDH Survivor Stories: South Korean Soldiers Massacre Nearly the Entire Village of Ha My

The story of Nguyen Thi Thanh

When 11-year-old Nguyen Thi Thanh’s woke up on the morning of February 25th,1968, she had no idea her life would change forever. Nguyen was going about her day as usual when she suddenly heard screaming coming from the far side of Ha My, a small coastal settlement of Quang Nam Province in central Vietnam. She turned in the direction of the loud shrills and saw smoke clouds filling the sky.

She immediately sprinted in the direction of the smoke to see what the source was. As she neared, she saw a group of soldiers with their guns drawn. Afraid and panicking, she ran back to her family’s house to tell her mother, Le Thi Tho, that the village was surrounded. “As I finished my sentence, [soldiers] poured into our house,” Nguyen recalled.

Later reports revealed the soldiers were members of the Blue Dragon Division, a notorious South Korean marine corps. After entering the Thanh home, they ordered her entire family, along with other villagers, into an underground shelter under their front yard. The ruthless soldiers threw grenades in after them, killing Nguyen’s aunt and her infant cousin instantly.

Nguyen says her mother tried to shield her and her brother. “‘We are doomed, my baby,’ Nguyen’s mother cried out. “My whole body was burning and then felt numb… I could see other people’s blood all over me,” Nguyen said. Nguyen’s eight-year-old brother lost a leg and eventually died of his injuries at the hospital.

Nguyen and one of her cousins, both severely injured, luckily survived by crawling to a neighbor’s for help. She says that after she escaped, the soldiers then burned her house down. “I could hear the popping and crackling sounds from burning bamboo. I smelt smoke, fire.”

More than 135 unarmed villagers in Ha My were killed that day, with only around a dozen villagers surviving. Although she says South Korean soldiers had regularly visited Ha My before, looking for communist Vietcong members, she has no idea why that day was different. “We don’t know why they were so aggressive that day. They even killed three and four-month-old babies.”

The massacre occurred during what was known as the Tet Offensive, when practically the entire countryside in southern and central Vietnam was deemed a “free-fire zone,” meaning that any location within it were designated as targets of destruction in response to the nationwide assaults by the Vietcong in urban areas controlled by South Vietnam and its allies. [1]

Nguyen did not witness the immediate aftermath of the massacre in Ha My, as she was taken to hospital in Da Nang to recover from her injuries. But her older brother told her the Marines dug a large, shallow grave for the many victims used and dropped napalm bombs from helicopters to destroy any evidence of the massacre. The Marines returned the next day and bulldozed the village.

South Korea’s government, which now has close economic ties with Vietnam, appears unwilling to engage in a review of its role in the Ha My massacre. South Korea’s ministry of defense sent a letter to Nguyen and 102 other survivors last September saying it has no record of any civilian killings carried out by its military in Vietnam, effectively distancing themselves from accepting blame for these and other horrific actions done by the South Korea military. [2]

Sources

https://apjjf.org/-Heonik-Kwon/2451/article.html [1]

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/extra/lhrjrs9z9a/vietnam-1968. [2]